Duty and taxes

A Quebec Superior Court rules against Kahnawake gas retailers who refuse to play tax collector on behalf of the government.

Timothé Huot says he is "beyond words."

That's following a Quebec Superior Court decision wherein judge Louis Crête ruled that First Nations in Canada have no right to refuse to collect taxes, even if they are themselves exempt.

"It basically rejects all the arguments brought forward by the Mohawks of Kahnawake," says Huot, a partner at the Montreal law firm BCF.

In Jack W. Leclaire, et al. v. Attorney General of Canada, et al., Huot represented 11 gas retailers from the off-island Montreal reserve of Kahnawake. The case is the culmination of a decade-long scuffle between the merchants and the provincial government.

National Magazine covered the arguments of the case in April.

The business-owners claim that, because they are status Indians, they have no obligation to collect sales taxes on gasoline bought on-reserve, even if the client is a tax-paying, non-status, Canadian.

Huot's arguments during the case focused on the centuries-old relationship between the Crown – the tax collector – and First Nations. He argued that the colonizer had always had the obligation – at times the fiduciary duty – to protect and enshrine the right of First Nations to trade freely, largely unfettered Canadian law. He leaned on Section 87 of the Indian Act as the premise for his case, but wound his way through what he called a sacred historical obligation.

"We took everything away from them and now the governments of Quebec and Canada are saying, ‘by the way, now we need you to collect taxes for us,’" says Huot, adding that the state of public infrastructure on the reserve does not merit any cooperation with the federal or provincial tax regime. ("The goddam postal company doesn't even deliver!" he says.)

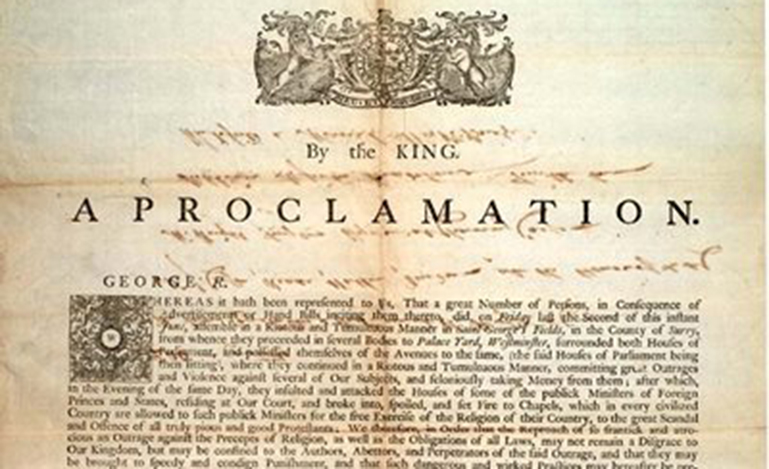

Government lawyers for Ottawa and Québec countered Huot's arguments by arguing that notions of trade have evolved since King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763. If Kahnawake is going to purchase fuel wholesale, and sell it back to Canadian consumers, they will have to charge all the applicable taxes.

Crête agreed entirely with the government. He wrote in his ruling that the retailers failed to prove that any "ancestral rights, Aboriginal title...rights issued by treaty or the Royal Proclamation" are at issue in this case.

"What it is, basically, is a very narrow view of Aboriginal law," says Huot. "It shows a complete absence of openness."

Huot is vowing to fight on. He has little hope that the case will get a different treatment at the Court of Appeal, but is optimistic that the Supreme Court might take a different view on the matter: "Our best friend is the Supreme Court," he says.

He points to two 2011 cases that, in his view, may support his case.

In Bastien Estate v Canada, the justices unanimously agreed – albeit for different reasons – that the estate of Roland Bastien, a Quebec artisan who lived on-reserve, did not have to pay interest on revenue generated from investing in his reserve's credit union.

The decision was passed down in a joint ruling with Dubé v Canada, a similar circumstance whereby a member of a Quebec First Nation invested in the credit union of a nearby reserve. The Canada Revenue Agency argued that he ought to pay taxes on the interest earned. The majority of the Supreme Court disagreed with that argument with Justices Marshall Rothstein and Marie Deschamps dissenting, as the credit union in the case was located on reserve other than the appellant's.

In both cases, the court clarified that Section 87 of the Indian Act should be held to protect the private property of a status Indian, so long as it has a determined connection to the reserve. Justice Thomas Cromwell, writing for the court on the Bastien Estate case, held that deciding to exempt income from taxes should be a two-step process.

"First, one identifies potentially relevant factors tending to connect the property to a location and then determines what weight they should be given in identifying the location of the property in light of three considerations: the purpose of the exemption from taxation, the type of property and the nature of the taxation of that property," he wrote.

While both cases offer some pretty clear direction that the Supreme Court tends to maintain a rather stringent view of Section 87, both dealt strictly with personal income. Huot would be asking the Court to determine whether or not that definition of tax-exempt property can be stretched to include the sale of goods to non-status Indians. Though Huot did make the case before the Quebec court that the system proposed by the province would, incidentally, tax the business-owners by making them responsible for any shortfalls in the sales taxes that they should owe.

Huot filed an appeal virtually immediately after the decision was passed down.