What does consent mean?

The SCC has given its blessing to the new rules for genetic testing. Now it's effectiveness hinges on the transparency of companies' testing practices.

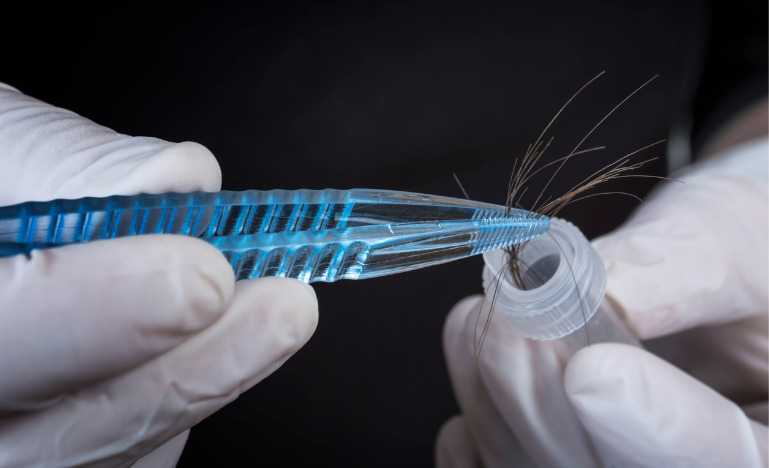

Canadians can breathe a sigh of relief. After a two-year legal saga on the constitutionality of the Genetic Non-Discrimination Act, or GNDA, the Supreme Court this month affirmed that the legislation is a valid exercise of Parliament’s competence over criminal law. Concerning privacy, the most significant aspect of the legislation is that it is prohibited for any person to collect, use or disclose results of an individual’s genetic tests without their written consent.

While the GNDA complements Canadian privacy laws with respect to consent, there are some differences in terms of language used and some of the exceptions outlined. Organizations must now audit their practices to give full effect to these laws and reconcile their differences. Meanwhile, consumers will need to consider several factors to ensure they remain in control with respect to their personal information.

Companies that offer health-related genetic tests should offer consumers user-friendly and intelligible privacy notices about their services. Consistent with their obligation of transparency, they must explain with a sufficient level of detail the stated purposes for the collection, use and disclosure of their personal information to ensure consumers can reasonably understand the scope of their consent. Since it’s essential consumers understand that they have all the information they need, it’s best to present the notice in a layered format that allows them to find particulars easily.

Next is the obligation to offer consumers the opportunity to provide “written consent” to the collection, use and disclosure, as required by the GNDA. Canadian private sector privacy laws generally contain a requirement to seek “express consent” for sensitive information such as genetic data. We’re talking here of a similar level of protection.

Consent should only be sought for explicitly specified and legitimate purposes. As a guidance, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) states that consent is valid “…if it is reasonable to expect that your customers will understand the nature, purpose and consequences of the collection, use or disclosure of their personal information.”

For genetic testing companies, obtaining written consent is more commonplace online with an easily accessible interface allowing an individual to consent. In practice, this means individuals should have the ability to clearly express their consent by checking a ‘Yes, I agree’ checkbox after being directed to a company’s privacy notice.

Should the personal information be used for any purpose incompatible with legitimate purposes, such as marketing, the individual concerned should be given a choice to accept or not these non-essential conditions, which materializes through an opt-in or opt-out option.

Consent should be an ongoing process and not a one-off, as it is common for companies to update their privacy notices with changes in law or privacy practices. For example, any material changes such as the use of information for a new purpose or the disclosure of information to a third party not initially contemplated merit the consumer’s attention.

It should also be easy for consumers to withdraw consent. However, if third parties such as research scientists who fall outside the scope of the GNDA use the information, consumers may want to know how to withdraw it. If the information is used in a research study and rendered unidentifiable as part of the final results, withdrawing consent to use the information may be impractical. It may, on the other hand, be relevant in cases where personal information may be re-identifiable. Consumers may want to look for these details in notices when consenting to these conditions.

In their external policies, companies should also notify consumers if third parties are used to process personal information, and describe the measures taken to protect it. They should provide details with respect to retention periods, and detail processes such as access or correction requests. To demonstrate compliance to consumers and regulators, genetic testing service providers must audit these companies and agree in writing to adequate representations and covenants relating to compliance with applicable law.

It is noteworthy that the GNDA does not apply to physicians, pharmacists or other health practitioners who provide health services, or to pharmaceutical or scientific researchers acting in the course of their studies. Individuals need to be made aware of these exceptions in the relevant notices that companies provide their consumers.

Canadian privacy laws add a few more exceptions which should be part of a genetic testing company’s privacy notice. The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) exempts other parties that may be privy to the information such as law enforcement and government bodies in the scope of their investigative functions.

Should the personal information be processed in another country for a variety of reasons, consumers should be made aware of this. Companies should specify in their privacy notices if they intend to use third parties in foreign jurisdictions to process personal information. Canadian businesses should carefully consider all relevant factors in deciding to do so. Should they decide that processing information in a different country is necessary or desirable, they need to notify consumers of the potential risks. If they are processing data in the United States, it’s important to inform consumers that their information may be accessible to U.S. law enforcement and national security authorities. As per the OPC’s guidelines, consent is then deemed to be respected as once an “…informed individual who has chosen to do business with a particular company, they do not have an additional right to refuse to have their information transferred.”

The legality of these scenarios has yet to be tested in the context of the GNDA. But where there’s no incompatibility between the GNDA and Canadian private sector privacy legislation, consent to these types of disclosures is obtained if Canadians are made aware of these risks before they hand their information over.

While the validity of the GNDA is a stepping stone in the protection of personal information, the effectiveness of privacy laws, including the GNDA, hinges on genetic testing companies’ practices. Being transparent, clear and detailed in privacy notices as well as providing the opportunity for consumers to give meaningful consent establishes a basis of trust with them and good faith relations with regulators.