In the weeks leading up to my 19-year-old daughter's attempt to obtain an operator's licence, I took her driving every night, like any attentive parent, so she could hone her skills. I’ve been driving for about 40 years now. The rules of the road haven’t changed a great deal in that time, the cars have improved immensely but, I must say, the drivers have become deranged.

Today’s driving experience is a dog-eat-dog, survival-of-the-fittest kind of thing. These weeks in the car with Kate have allowed me to point out the driving habits of other motorists as a matter of instruction. The standards prescribed by provincial legislation function only as loose guidelines, observed more in the breach or when a patrol car is in sight.

Consider the left-hand turn on a red light. The theory underlying the law is that a vehicle should not be stranded in an intersection and so a single vehicle is allowed under law to turn left after the light has changed to red. But it is now common for a second or even a third car to charge through. The message: Clear the track: My rights are more important than your rights.

Driving today is like reliving the 1975 cult action classic Death Race 2000 (starring the late David Carradine) or to use a more current analogy, Need for Speed (with Jesse Pinkman from Breaking Bad in the lead role). Defensive driving is for chumps and the principle philosophy seems to be that I need to get ahead of the other guy because I’m entitled and that’s the way it is.

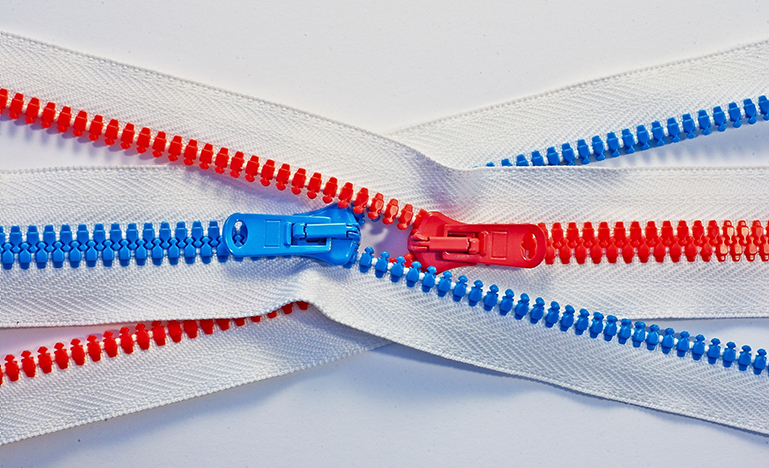

This brings me to the idea of the zipper merge. It is a driving manoeuvre that promotes efficiency, but relies on collaboration. When merging is required because of road construction, for example, or because that’s the way the traffic has been engineered, both lanes are used with vehicles merging at the last possible point and drivers in each lane taking turns.

It is a perfect example of co-operation or, if you will, of the Spockian theorem that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the one. But it is not known or understood in many urban environments where most drivers will merge early, creating traffic delays; if attempted, the motorist who zips down the free lane to the merge point is labelled a d-bag.

The City of Saskatoon, however, is an urban centre ahead of its time. It has proclaimed zipper merging as a means of reducing traffic congestion and vehicle collisions at construction sites. Saskatoon actively promotes the technique through signage and an awareness campaign that includes an instructional video on its website.

All this talk of driving is, of course, my metaphor for the way we settle legal disputes in Canada. In some 30 years of being a lawyer, I’ve litigated in every court. It’s always a contest of wills, of dishing out and taking hits, of getting ahead and getting delayed, of being aggressive and competitive and pulverizing your adversary into submission, or being pulverized.

A while ago, a lawyer acquaintance of mine who had been quite a successful litigator, told me he was changing careers. He said he couldn’t take the aggression, stupidity and waste any more (his words). I don’t know whether he was talking about the system, lawyers, or clients in general, or maybe all three. I imagine it’s not unlike the lassitude I feel after driving.

By contrast, mediation is gaining more purchase in our legal system. It is successfully executed when the parties take a conciliatory approach, have a well-defined process and a common objective. As such, mediation is more like the zipper merge.

I’ve been fortunate enough to experience mediation as a lawyer, a client and a mediator. It hasn’t always worked but the times that it did was because each party recognized the legitimacy and rights of the other.

By way of aside, I am writing this column while holidaying in Italy. We have just come from a stint in Rome. Now there’s a city with a lot of traffic. It seemed to my untrained eye that the drivers drive randomly and don’t pay much attention to the lanes. The ubiquitous scooters and motorcycles zipped between rows of cars and manoeuvred to the front at stop lights.

Somehow it all seemed to work. I didn’t see any collisions and no one got mad. Everyone understood the rhythms and patterns of the traffic and the need of each person, including pedestrians, to get where they want to go.

As it happened, Kate got her driver’s licence on the first try. I like to think that her defensive-driving chump of a dad had a hand in that.