No peaceable enjoyment

A Quebec Superior Court decision on rent reduction in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic could have repercussions across the country

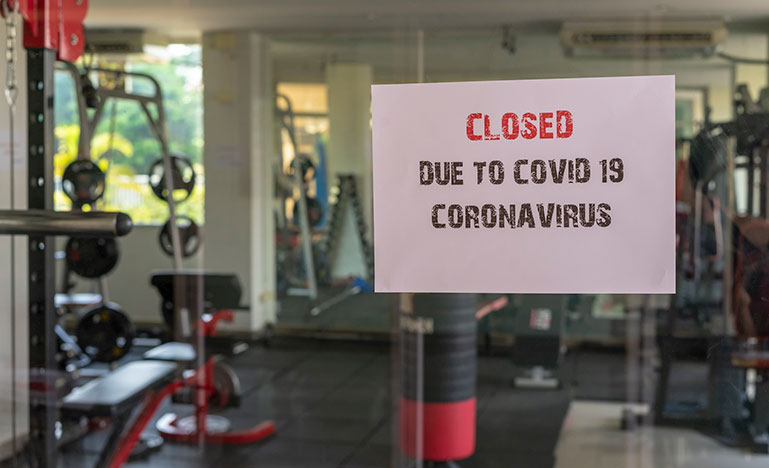

In Hengyun International Investment Commerce Inc. c. 9368-7614 Québec inc., Justice Peter Kalichman ruled that the province's orders to close commercial facilities, and gyms in particular – the business in question in this case – created a situation where the landlord was unable to provide "peaceable enjoyment" of the premises. The lease agreement also included a force majeure clause that was invalidated as a result.

"The Landlord's fulfilment of its obligation to provide peaceable enjoyment of the Premises from March through June of 2020 has not been delayed; it simply cannot be performed," wrote Justice Kalichman. "Consequently, the Landlord cannot insist on the payment of rent for that period and paragraph 13.03 of the Lease does not apply."

"It's absolutely a worrisome case," says Christina Kobi, partner with Minden Gross LLP in Toronto. "My view, partially informed by my litigator colleagues, is that it would be wise and prudent to be concerned about this case elsewhere if you're a landlord."

Kobi says that a sympathetic judge or court may look to the Hengyun ruling even if it is based on Civil Code of Québec provisions. On the other hand, one that is less sympathetic to the tenant can easily distinguish the facts and raise differences between common law and civil law.

"There are many in the legal community who view this as wrongly decided, and it will be interesting to see how it plays out if it gets appealed. But rightly or wrongly decided, judges and courts who are sympathetic to a tenant – especially in this COVID era – if they look for a means to help the tenant, this may be used for that," says Kobi. "That is what everyone is very nervous about."

According to Kobi, the Civil Code obligation for "peaceable enjoyment" is not identical to a common law or contractual obligation for "quiet enjoyment." But there is enough overlap that a judge may be able to lean on the decision.

Kobi adds that tenants are "jumping for joy," hoping that this decision can give them leverage in rent relief negotiations.

"Both parties are now coming to negotiation, even outside of Quebec, with this added bit of information that makes them excited or nervous, depending on who you are," says Kobi.

Howard Sniderman, partner with Witten LLP in Edmonton, says that the court's analysis and the decision was a reference to a provision in the Civil Code around the definition of "superior force," as it related to the health authority's decree to close all gyms in the province.

Sniderman was part of a group that was lobbying the Alberta government around what is now the new Commercial Tenancies Protection Act that just received royal assent, but has not yet seen any regulations passed.

"Imputing a government edict as the intent and act of the landlord – I have big problems with that," says Sniderman. "That's a magic leap of faith and of law that the judge made, which doesn't seem to be warranted, even taking into account the unique situation by virtue of the fact that we're dealing with a Civil Code-defined term that doesn't exist in common law jurisdictions."

Sniderman says that the court didn't comment on what is likely a boilerplate clause in the lease in question, which would obligate the tenant to conform and comply with the law as it may evolve.

"Here we had an evolution of law – a public health edict," says Sniderman. "That, in and of itself, couldn't really be laid on the doorstep of the landlord as amounting to a breach of the covenant to provide 'peaceable enjoyment.' I'm not sure how you impute on the landlord that it's breached the covenant by virtue of the tenant complying with its contractual obligation to comply with law."

Sniderman says that the court did at least note that the gym and the tenant had the benefit of access to the premises – they simply weren't able to open to the public.

"The judge paid lip service to the benefits still accruing to the tenant, notwithstanding the public health edict, this doesn't in any way, shape or form, help the bootstrapping attempt by the judge to equate the public health order to the act or intent on the part of the landlord to breach the covenant of peaceable enjoyment," says Sniderman. What's more, he sees several avenues for appeal, though he suspects it may be too costly for the landlord to pursue.

Kobi also has problems with the logic in the decision.

"The court held that this government-mandated closure in the landlord's breach of the Civil Code requirement, and it's a stretch for me," says Kobi. "The fact that the landlord didn't [contract out of the requirement] has the court taking the view that they didn't, so they go with the risk of having that in there.

"At the end of the day, there is no question that the court was looking to help the tenant here, and there are twists and turns to make it happen," says Kobi.