The ongoing effort to legislate judicial oversight of solitary confinement

‘It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails:’ Nelson Mandela

Those who’ve been locked up in isolation for weeks, months or even years recall doing almost anything to pass the time.

Often, the only breaks are meals slid through a metal slot, a shower, perhaps a brief walk, and a chance to speak with a parole officer, elder, or nurse.

Segregation has well-documented impacts such as panic attacks, assaults, crushing loneliness, self-harm, paranoia and delusions.

‘Every time I asked for help, I got more time’

“Some people, especially guards, think it doesn’t affect people, but I lost my mind in seg,” says Tona Mills, 53, who is now in palliative care in Halifax.

“I worry the cancer I have today is partly because I was stuck inactive in seg so long.”

Like many other Indigenous women, she traces her time behind bars – including most of a decade in solitary confinement – to the mental health toll of traumatic abuse growing up. One of her first arrests was for breaking into a school to escape being raped.

Tona Mills, left, during a recent visit with Senator Kim Pate.

Once she was finally released into the mental health system, Mills was diagnosed with isolation-induced schizophrenia.

“Every time I asked for help, I got more time,” she says.

“Other friends have died the same way. I think it affects many, but they die after prison, so nobody pays attention.”

The latest push for oversight

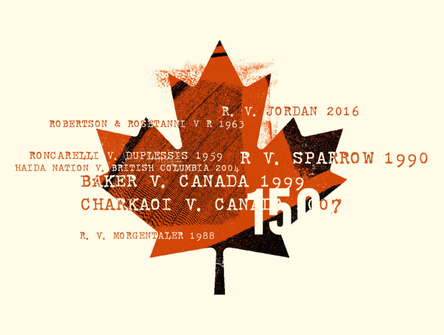

In October, the Senate voted to send Tona’s Law, Bill S-205, to committee for study. It’s the latest push by the upper chamber over the last decade to legislate judicial oversight of solitary confinement.

The bill would amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act to require a Superior Court order for keeping someone in isolation for longer than 48 hours.

It would also mandate that anyone with a disabling mental health issue be moved to a hospital, and provide more support for disadvantaged and minority groups.

An earlier version of the bill reached the House of Commons but died on the order paper when Parliament was prorogued in January.

Solitary confinement is generally defined as spending 22 hours or more a day alone in a cell without meaningful human contact. More than 15 consecutive days in such conditions is deemed torture under international standards such as the United Nations’ “Mandela Rules.”

Appeal courts in B.C. and Ontario in 2019 found that the CSC’s use of administrative segregation violated sections seven and 12 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The Liberal government responded with Bill C-83 to replace the old regime with “structured intervention units” or SIUs.

It was hailed as a fresh approach that would offer a minimum of four hours a day outside isolation cells, including two with “meaningful human contact.”

No judicial justification required

Senator Kim Pate, who sponsored Bill S-205, highlights what critics say was a crucial flaw in the 2019 overhaul: the government rejected a Senate amendment that would have forced the CSC to justify extended isolation in court.

Instead, the government struck an SIU Implementation Advisory Panel, whose mandate ended after five years following a series of critical reports based on the CSC’s own statistics.

Its final report last December concluded: “The picture painted by the data consistently shows that the practice of solitary confinement continues, and vulnerable groups appear to be especially at risk of experiencing its negative effects.”

They include Indigenous and Black people, along with those with mental health issues.

The panel’s reports from 2020 to 2024 repeatedly found that hundreds of SIU stints lasted 61 days or more, including 434 in 2023 and an estimated 534 in 2024.

The numbers did not reflect “split stays” when someone is briefly removed from SIU and then readmitted, restarting the count.

About 40 per cent of those placed in SIU stayed for more than a month, not unlike rates seen under the old administrative segregation regime, the panel found.

Mental health needs shuffled off

The panel has also reported that of inmates with multiple SIU stays, about half of those with significant and deteriorating mental health needs were moved to SIUs around the country.

“The disruption to programming and stability that this creates for people who clearly need stability and programming is alarming.”

Moreover, “CSC’s data demonstrate that many prisoners do not receive anything close to four hours daily out of their cells,” the panel found.

It described the government's response to its many recommendations as “largely inadequate.”

The panel’s conclusions pointedly note that a mandatory parliamentary committee review of Bill C-83’s provisions, which was to start in 2023, was long overdue.

“The Government of Canada must demonstrate that it is serious about ensuring CSC operations are lawful and Charter-compliant.”

A spokesperson for the CSC said no one was available for an interview, but in an email, described SIUs as a “historic transformation.”

“SIUs are used only as a last resort, when no reasonable alternative exists, following efforts to manage inmates safely within the mainstream inmate population.”

The CSC cites the units’ improved programming and Indigenous support, a zero-tolerance policy for abuse by staff, and an increase in successful releases (meaning no readmission within 120 days) to 63.1 per cent in 2024-25, from 59.9 per cent in 2023-24.

Vulnerable to interference and reprisals

The correctional service also refers to oversight through the public safety minister’s appointment of 12 independent external decision-makers (IEDMs), who review long SIU stays and complaints.

However, one of those former IEDMs, Janine Lespérance, publicly raised concerns about transparency and accountability after her contract was not renewed.

“IEDMs are vulnerable to interference and reprisals arising from institutional resistance to external oversight,” she wrote in an article last May for Policy Options.

“An objective inquiry is needed to … determine whether those whose decisions were less favourable to CSC have been pushed out.”

Isolated ‘for years and years and years’

Pate regularly visits penitentiaries. She has taken almost 50 senators along with her to meet inmates, staff and see conditions for themselves.

Recent trips to the Nova Institution for Women in Truro, N.S., Stony Mountain Institution in Manitoba and the Regional Psychiatric Centre in Saskatoon showed the starkly disproportionate segregation of Indigenous women in SIUs, she says.

One woman has lived in isolation “for years and years and years because of her mental health issues.

“She’s actually now detained under a mental health warrant – not even under sentence – and hasn’t been for many years.”

Other inmates with cognitive disabilities or dementia are isolated “not because staff are trying to be cruel or punitive, but because it’s the easiest way to monitor them.”

“There’s layer upon layer of injustices that we see in our segregated units, sometimes called SIU, sometimes mental health observation, sometimes voluntary limited association or therapeutic ranges,”Pate says.

“These folks, if they don’t die in custody, are released into the community with the very same issues, and probably more” than they had going in.

Accountability ‘black hole’

Data tracking for SIUs by another name is an accountability “black hole,” says Debra Parkes, a criminal law specialist at UBC’s Allard School of Law.

She has worked on prisoner rights law for 25 years. There are times when people must be isolated for safety reasons, she stressed.

But the government could be looking at best practices in New York City and elsewhere that focus on de-escalation, life skills and mental health care. The CSC has a history of cutting reliance on isolation when it’s in the headlines, she says.

Parkes blames a “law-and-order” fixation for the persistence of methods that are more costly and less effective for public safety, let alone rehabilitation.

Politicians are loath to be seen as “soft on crime,” she says, adding real change may take another constitutional challenge.

“That’s likely what’s going to be happening now. We’re going to be back in litigation about this.”

Toronto lawyer Jeffrey Hartman filed suit in 2020 on behalf of two federally incarcerated men, alleging the CSC was not following the law or its own policies.

The class action was later dropped “not for lack of merit, but because we didn’t want to litigate it for a decade,” Hartman said in an email.

For Tona Mills, her dying wish is that someone in power will ensure others don’t suffer as she did.

“Even a few days in seg can destroy people. Please help stop the hurt and help people live.”