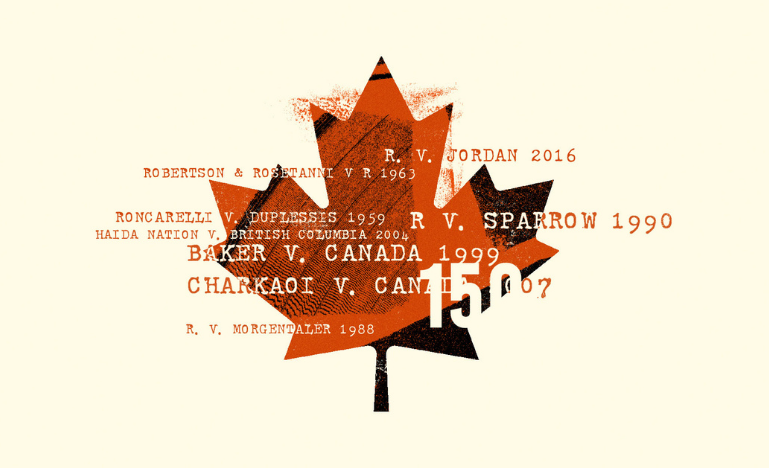

The cases that made their mark

The Supreme Court of Canada marked its 150th anniversary in 2025, so we asked former justices about the cases that stand out to them as the most important

The Supreme Court of Canada marked its 150th anniversary in 2025. As the country’s final court of appeal and the only bilingual and bijural apex court in the world, it has handed down thousands of decisions over the years.

We asked former justices which one they think stands out as the most important.

Reference re Secession of Quebec (1998)

Former Justice Rosalie Abella says that, given the numerous decisions made since 1875, picking one isn’t easy.

“It's really like saying which of your children do you like the best. I can name a dozen that I think are extraordinarily significant in how they've reshaped what Canada is and is becoming,” she says.

“But I think the secession reference, without any doubt, is one of the most consequential decisions the Court’s ever decided.”

Following the 1995 Quebec referendum, the case required the Court to consider whether the province had the right to unilateral secession. It found that Quebec could not unilaterally separate from the rest of Canada. Doing so would violate Canadian constitutional law and international law principles. However, if Quebec were to vote clearly in favour of secession, Canada would have a duty to negotiate.

Abella says the decision stands out because it dealt with a national identity crisis and figured out a way to create a legal template for moving forward from the weight of the precipice.

It also set out the components of Canada's constitutionalism, discussed what constitutes democracy in this country, including minority rights and democratic principles. This established a path forward for how Canada should see itself in a legal framework.

“It really represents not just a rule of law, but a just rule of law, which is both aspirational and defining,” Abella says.

“I think it's a beautifully written decision, and it explains the role, not only of Canadian constitutional law, which I was really impressed with, but the reliance on international law and the values of international law that had developed in global terms since the Second World War. It's just a masterpiece of judicial writing and thinking in my view.”

Abella was appointed to the top court in 2004, so she says she “can’t take even the tiniest bit of credit” for it.

Former Justice Frank Iacobucci can.

A member of the Court from 1991 to 2004, he says the reference stands out for him because it dealt with the very makeup of Canada, statehood, and a question that was not expressly answered in the Constitution.

It put a great challenge before the Court, and considerable consequences would flow from the decision.

Before going into the law, Iacobucci had taken an undergraduate course in federalism. As part of that, he studied the American experience of constitutional making, read the Federalist Papers and President Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural speeches. His studies encompassed the secession of Southern states and the creation of the Confederacy. That was triggered by Lincoln's election in 1860, as some Southern slave-dependent economies saw it as a threat to slavery. Ultimately, this led to the American Civil War.

“When you have an issue of secession, that could be a consequence. Without any legislative framework, it's dangerous, it's unpredictable as to what would happen,” Iacobucci says, admitting he personally was “absolutely” concerned with the pressure of the decision and what could flow from it.

He stresses he doesn’t say that with any desire for or entitlement to undue recognition.

“That's not the point I'm making. It’s why we put more effort into that decision than any other one in the over 13 years that I was on the Court. Because it involved all of us — not just all of us in that courtroom on the bench, but our country. Everyone was affected by it.”

Former Justice Ian Binnie had been appointed to the Supreme Court just a month before the secession reference was heard, and clearly recalls how he felt sitting on the bench.

“(I) felt a sense of responsibility equal to the challenge that was presented,” he says.

“The stakes were very high, and it was important that the Court got it right.”

Iacobucci thinks they did. He recalls the unbelievable media coverage of the decision.

“To be candid, it wasn't all flowing of bouquets of acclaim and praise. There was criticism, but it was civic and respectful, because it's not an easy issue,” he says.

“Different parties claimed victories, opposing parties claim victories. That's a signal that maybe you've got something close to getting the right approach.”

The decision also garnered attention beyond Canada’s borders.

“It's been cited internationally,” Iacobucci says.

“It has been recognized as the most challenging set of issues in different parts of the world, including the US.”

Reference re Supreme Court Act, ss. 5 and 6 (2014)

When Marc Nadon was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada by former Prime Minister Stephen Harper, an application was launched by Toronto lawyer Rocco Galati and the Constitutional Rights Centre Inc. to have him removed.

The challenge centred on the fact that Nadon, a Federal Court of Appeal judge, was not a member of the Court of Appeal or the Superior Court in Quebec, nor was he a current member of the Bar of Quebec, as required by the Supreme Court Act. Therefore, the claim asserted, he was ineligible.

The case ultimately came down to an interpretation of sections 5 and 6 of the Supreme Court Act. Seven justices sat for the case.

“Obviously, Justice Nadon couldn't sit, and Justice Rothstein, who had been a personal friend when they were both on the Federal Court, thought he should recuse himself,” says former Justice Michael Moldaver, the lone dissenter in the case.

The majority took the position that sections five and six precluded Nadon from being appointed to the top court as a member of the Quebec contingency.

However, it was the second point that arose that is the crucial aspect of this case, Moldaver says.

Parliament had amended sections five and six of the Supreme Court Act to cover off the situation Nadon found himself in. The Court had to decide if that legislation was valid.

“To make a long story short, the Court decided that, over time, and particularly with the Constitution Act of 1982, it had been constitutionalized as an institution,” Moldaver says.

“So, to change the eligibility requirements of any member of the Court, or to make any major significant changes to the number of judges, for example, Parliament could not do it unilaterally.”

Instead, Parliament had to go through the amending formulas set out in section 41 of the Constitution Act, which requires unanimous approval by the House of Commons, the Senate, and all 10 provinces to amend the Supreme Court Act on a question concerning the composition of the court.

In a nutshell, the Court was clear that Parliament is significantly restricted in terms of making changes to this piece of legislation.

“I think that's a very important case, particularly in today's times, and what we’re seeing elsewhere,” Moldaver says of jurisdictions around the world where governments have faced criticism for altering court eligibility and appointment rules to favour politically aligned candidates and gain control.

“It makes us pause and think that under our law, Parliament cannot, on its own, change the complexion of the Court or the eligibility requirements of the Court, and basically, the composition of the Court.”

After all, he adds, “When you lose the vital component of independence, all is lost.”

R. v. Stinchcombe (1991)

Former Justice Morris Fish practiced criminal law before moving to the bench, and in that realm, Stinchcombe stands out as the most important decision.

“No judgment of which I'm aware did more to level the playing field between the Crown and the accused, particularly an accused with limited means, which the great majority of accused are,” he says.

That point was driven home to him in a case that dates back to 1965. At the time, he was representing a pro bono client facing a murder charge in Montreal. Fish wasn’t involved in the early stages of the case, so he wrote a letter to the chief prosecutor, Richard Shadley.

“The letter said that we wish to place ourselves on record as having requested on several occasions that you provide us with copies of all statements in writing, or reduced to writing, by all witnesses whom the Crown intends to call. We were particularly anxious to have a copy of the statement made by the eyewitness, on whose evidence the guilt or innocence of the accused would be determined,” Fish recalls.

He says this evidence was essential, as they had no means to investigate.

“The letter did me no good. They gave us nothing at all,” Fish says.

“The fact that (Shadley) didn't respond at the time was par for the culture at the time.”

The law in Canada at the time did not require the Crown to disclose to an accused the evidence it had in its possession, even if it might have helped the accused establish their innocence.

Fish notes that decisions rendered by the Ontario Court of Appeal in the 1970s and 1980s held that the Crown was not obliged to provide all the information it had gathered in relation to a charge to the accused.

“So this persisted.”

Fast forward 30 or 40 years, Shadley was being honoured by the Quebec bar at a conference Fish was the honorary chair of, and trotted out the letter. In making the request he had more than 25 years before Stinchcombe, Shadley said Fish was “prescient.”

Fish told Shadley he was still waiting for a response to his letter because he had never heard back from him.

It was Stinchcombe that changed everything. Since 1991, the Crown has been obliged to provide the defence with the information it has gathered, whether or not it intends to produce or use that evidence, as it could conceivably be used by the defence to launch an investigation or to counter and cross-examine Crown witnesses.

“To me, Stinchcombe had a greater impact on the practice of criminal law throughout Canada than any other single judgment of the Supreme Court of which I'm aware,” Fish says.

He was appointed to the top court in 2003, after serving for 14 years on the Quebec Court of Appeal; therefore, he never practiced as a defence attorney after the decision. But he says defending clients pre- and post-Stinchcombe is “absolutely” night and day.

Roncarelli v. Duplessis (1959)

Frank Roncarelli was a successful restaurant owner in Montreal and a practicing Jehovah's Witness who was very active in that community. Over three years, he bailed out more than 300 fellow Jehovah's Witnesses who had been arrested in a time of tension with the dominant Roman Catholic community.

Some government officials saw Roncarelli as a disruptor of the court system and civil order, whose restaurant shouldn’t be entitled to a liquor licence. This included Montreal’s chief prosecutor, who contacted the premier, who in turn contacted the chair of the Quebec Liquor Commission, who revoked Roncarelli’s liquor licence forever. It was a warning to others that they would also lose their provincial “privileges” if their religious activities persisted.

The case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court after Roncarelli sued for damages. Former Justice Marshall Rothstein says while nearly all the judges contributed to the decision, Justice Ivan Rand’s reasons stand out as “iconic.”

Rand found that the Alcoholic Liquor Act, under which the Commission chair acted, provided that the liquor board could, in its discretion, cancel a licence. The legislation was broad, and if someone just read the words, it would be fair for them to think the Commission had simply exercised its discretion.

However, just reading the words isn’t enough.

“Justice Rand said there's no such thing as absolute and untrammelled discretion, and that there has to be a reason for an action that is related to the purpose of being of the legislation,” Rothstein says.

In setting out the principle that no public official has ”absolute and untrammelled discretion,” the landmark case established that all exercises of public power are subject to legal limits and the rule of law.

Today, the case would be decided under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, specifically the provision of freedom of religion; however, Rothstein says it remains the best statement on the fact that there are limits on decision-makers’ discretion.

“That's so fundamental that it carries through today in all administrative law cases where a government board or a tribunal is exercising its discretion. That discretion has to be exercised with heavy regard to the text, context and purpose of the legislation.”

Rothstein notes that this is a case where it wasn’t clear at the time just how far-reaching its ramifications would be.

“When you write a judgment, you don't always know how important it is. Roncarelli was just a simple damages action against the government, and it turned out to be an iconic, seminal case because of the language used by Justice Rand in explaining why what the government did was unconstitutional.”