TransMountain: Keeping to a tight schedule

In agreeing to hear six instances to appeal the re-approval of the pipeline, the Federal Court concludes that the adequacy of consultations meet the "fairly arguable" standard for leave — and tries to be mindful of the timeline.

Like Bill Murray in that movie Groundhog Day, the c-suites of Canada’s energy sector must have felt like they were stuck in a time loop, doomed to live the same events over and over.

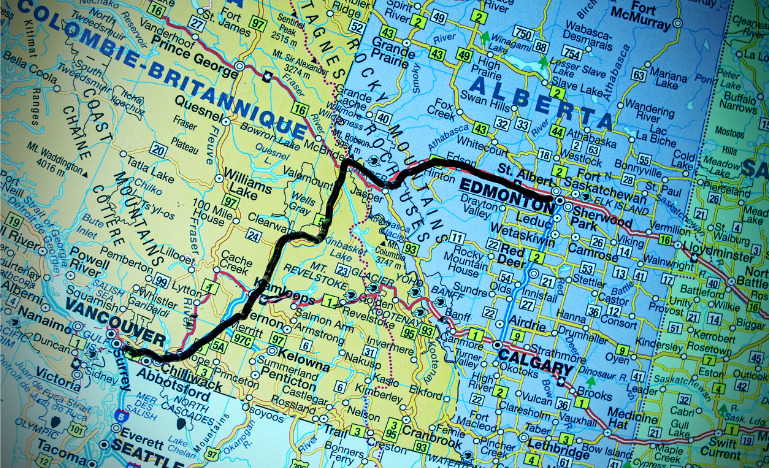

On September 4, the Federal Court of Appeal issued a ruling on a dozen applications for judicial review of the federal cabinet’s decision to approve construction of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project. The $7.4 billion expansion will (if it’s ever built) carry nearly a million barrels of oil per day from Alberta to B.C.'s coast, breaking a bottleneck in the Alberta oilpatch’s shipping routes.

Justice David Stratas took a page from Solomon and cut the bundle in half — rejecting six applications and clearing the other six to be heard simultaneously. His decision doesn’t call a halt to construction, which has started already. And Justice Stratas is trying to expedite the process with an aggressive timeline: the parties were given just seven days to file the paperwork.

But everyone remembers what happened a year ago, when the Federal Court of Appeal shut the project down. Then, as now, the government was accused of conducting half-baked consultations with affected Indigenous communities. The reaction from many lawyers working in resources law has been one of rueful resignation.

“It’s surprising, but also not that surprising,” says Brittney LaBranche, an associate at Burnet, Duckworth and Palmer LLP in Calgary who specializes in oil and gas transactions.

“It adds an element of risk that industry hates, regardless of whether construction is affected or not,” says Evan Dixon, a partner at Burnet, Duckworth and Palmer LLP who practises administrative, regulatory and environmental law for energy sector clients. “It introduces uncertainty, anxiety, which project proponents don’t like.”

The appeal court ruling also introduced what looked to a lot of people like an element of farce. The applications for judicial review going forward target the adequacy of the Indigenous consultation process — the matter of whether the federal government fulfilled its “duty to consult” as required by law. Counsel representing the federal government opted not to introduce evidence in support of the consultation process.

“It may be that that was a strategic decision on the government’s part, to assume that leave to appeal would be granted regardless because there’s a relatively low threshold for leave,” says LaBranche.

If the feds were guessing that at least a few of the applications would be approved, they might have concluded they had little to gain by defending the consultation process in court — and much to lose politically by publicly opposing the efforts of Indigenous communities to block the project in an election year.

And affected Indigenous communities aren’t all on the same page. Some back the Trans Mountain expansion as a job-generator, while others oppose it as a mortal threat to their land and water. "That makes it very difficult for this government that wants to have improved relations with all Indigenous groups,” Brad Morse, dean of the law faculty at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, B.C., told CBC News.

It’s also possible the feds assumed that, since the Federal Court of Appeal almost never publishes its reasons when it grants leave to apply for judicial review, they could opt out of the argument without anyone noticing.

That’s not what happened, of course. The appeal court not only stated its reasons; it said it was compelled to do so because the federal attorney general did not defend the consultation process — and the applicants were entitled to a public explanation of the court’s decision.

Justice Stratas also concluded that, in the absence of federal evidence, he couldn’t complete his analysis of the applicants’ critiques of the consultation process — which, again, led him to grant leave.

So what happens now? From the perspective of the project’s current owner, the Government of Canada, the appeal court’s decision could have been much worse. Justice Stratas rejected applications that attempted to “re-litigate” environmental aspects of the project on which the courts already had ruled. He also reminded the applicants that “duty to consult” doesn’t give anyone a veto. And he appears sincerely determined to get the applications for judicial review heard quickly.

“Given that the Crown did not file any evidence and has stated its intention to vigorously defend the consultation process, the Crown believes that the consultation was adequate in the circumstances,” says Dixon.

Matthew Kirchner of Ratcliff and Company LLP is representing two of the appellants: Squamish Nation and the Coldwater Indian Band. He says the appeal timetable itself might have an impact on whether the parties apply for injunctions.

“It remains possible that some of the parties will apply (for injunctions),” he says. “I know Squamish is considering it.

“An injunction is an interim measure which just maintains the status quo until the full hearing of the court challenges. (So) an application for an interim injunction may not be necessary, depending on the schedule for the judicial reviews.”

In other words, everything depends on those reviews — how, and how quickly, they conclude. The project may be in better shape than it was when the court stopped it cold in August 2018 — but it’s not out of the woods yet.