“Canada needs to honour its word”

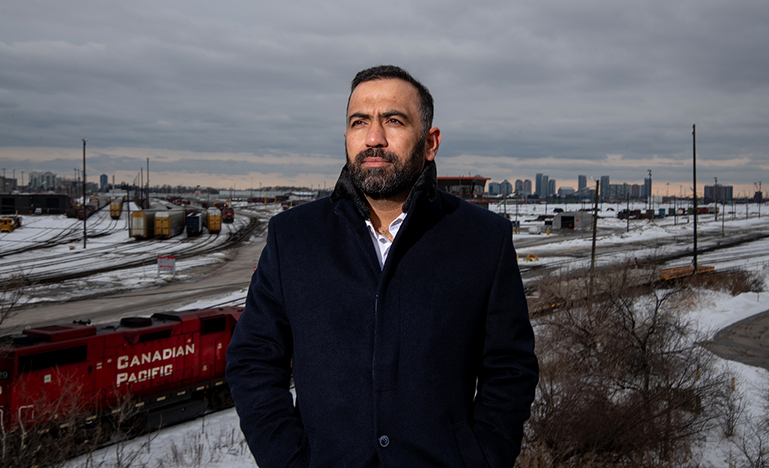

Afghan lawyer Saeeq Shajjan and several Canadian law firms are desperately urging the federal government to speed up the immigration process for legal professionals trying to flee Afghanistan.

Late last year, the Taliban’s long list of domestic targets got much longer.

According to local reports, Taliban forces entered the offices of the Afghan Independent Bar Association in Kabul in late November and ordered staff members to leave. The association’s records — including the names and addresses of Afghan lawyers — are now in the hands of people eager to hunt down every last Afghan professional who worked with the coalition of nations that drove the Taliban from power two decades ago.

“As soon as the Taliban knows that you worked for a foreign diplomatic mission — it doesn’t matter what the work was — they brand you as a spy,” said Saeeq Shajjan, an Afghan lawyer who, until recently, ran his own firm in Kabul.

“And the penalty for spying is death. And they kill you on the spot.”

Shajjan’s firm worked for the Canadian mission in Kabul before the country fell to the Taliban. The work was varied — everything from dealing with local landlords to fending off people looking to make a quick payday by ramming a diplomat’s car. “Through that work,” he said, “we were exposed as having a professional relationship with the Canadian mission.”

Shajjan applied to come to Canada at the end of July, 2021, as did most of his colleagues. Friends with American passports got him and his family (wife, three children, parents and siblings) to Qatar. On Sept. 2, they were all on a flight to Toronto.

“We were very, very lucky,” he said. His partners and a senior associate got out but they had to leave their families behind. Another colleague made it to Islamabad. Twenty-nine members of his staff remain in Afghanistan, hiding in a state of mortal terror.

“This is what a lot of us went into the law for in the first place,” said Carla Potter, a partner with Cassels in Toronto. She, her colleagues and several other Canadian law firms have taken on the daunting task of expediting the immigration process for legal professionals still stuck in Afghanistan.

It hasn’t been going well. “We were calling the IRCC (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada) hotline over and over, and it quickly became clear that we weren’t getting anything beyond cookie-cutter, perfunctory responses,” said Ardy Mohajer, also a partner at Cassels. “They kept telling us that they hadn’t received applications, but none of the people we’re in contact with have even managed to get that far.”

“We know that resettling these people is no small task. But we’re seeing no signs of progress,” said Potter. “We’re talking to 36 people in Afghanistan who still aren’t in IRCC’s system, and not for lack of trying.”

Shajjan and his colleagues are exactly the kind of people the federal government said it had in mind when it introduced a special immigration program for Afghans who had worked alongside Canadian soldiers and diplomats.

“It’s frustrating. I was led to believe that the government of Canada would give top priority to those who worked with the Canadians,” he said. “No one had a deeper relationship with the mission than us. But we’ve been waiting for good news since August.

“We’ve submitted documentation proving our professional relationship with the mission. We still haven’t heard the news we need to hear.

“We put our lives on the line. Canada needs to honour its word.”

For Afghan civilians hiding from Taliban retribution, home is a series of borrowed safehouses that must be swapped every week or so. Staying underground means steering clear of family and friends, regardless of circumstances.

“One of my colleagues couldn’t take his sick mother to the hospital,” said Shajjan. “Another has a wife in hospital who was ill and just gave birth — he couldn’t visit her.

“They move from place to place, province to province, staying with friends or relatives. I lose contact with one of them and begin to worry, then they get in touch and say they had to destroy their cellphone or move to a new safehouse.”

“The safehouses are falling,” said Thiago Buchert, a Halifax-based immigration lawyer who has been fielding frantic messages from Afghans trying to escape.

“The Taliban have been taking bullet-riddled corpses to police stations. The international media has moved on. The economic situation in Afghanistan is getting worse and famine is a real possibility now.”

Shajjan said the Taliban appear to be working down their list of targets — and lawyers may be next.

“Targeted killings are seldom reported in Afghanistan now, especially since so many journalists have fled,” he said. “Right now, they seem to be going after former Afghan army personnel, police officers. Once they’re done with those people, they’ll start going after the professional class, the lawyers and judges.

“It’s started already. It’s getting worse.”

Some law firms have issued appeals to the federal government directly. An open letter signed recently by representatives of several large firms and addressed to the federal cabinet calls on Ottawa to step up its efforts.

“Many vulnerable Afghans remain in hiding while others languish in precarious and untenable circumstances abroad with no clear pathway to secure resettlement,” says the letter, which went to the offices of Immigration Minister Sean Fraser, Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly and Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino recently. “We must do more.”

The letter says the federal government should devote more resources to the rescue effort, set up a special cabinet committee to encourage information-sharing between departments and ease the application requirements in special circumstances.

“The issue really is the backlog. [But] clearly some other measures are needed,” said Hugh Meighen, a partner at BLG, which endorsed the letter.

“There are certain requirements for applications that may not be workable for people in third countries, certain documents that may not be practical to obtain for people in hiding. We think these circumstances call for a bespoke approach. It shouldn’t be simply a box-ticking exercise.”

For Afghans in hiding or living as refugees in third countries, it can be exceedingly difficult to assemble the paperwork required to get an IRCC file started. The Canadian Bar Association’s Immigration Law Section recently called on Ottawa to waive the regulatory requirement that Afghans seeking resettlement in Canada through private refugee sponsorship first obtain formal refugee status.

For the lawyers and support staff who have been working on this file evenings and weekends for months now, the lack of visible progress is vexing.

“The entire firm is behind this, from the partners to the associates to legal assistants and articling students,” said Mohajer.

“It’s been five months since we started. I’d be lying if I said I hadn’t expected some actual progress by this point. It’s disheartening.”

For Shajjan, the anxiety cuts deeper. Every day that passes without good news from his Afghan colleagues is one more day to imagine the worst.

“I’ll be honest with you,” he said. “Every morning I get up and check my email. Every time, I’m expecting to hear that one of my colleagues has been taken.

“It could happen any day.”