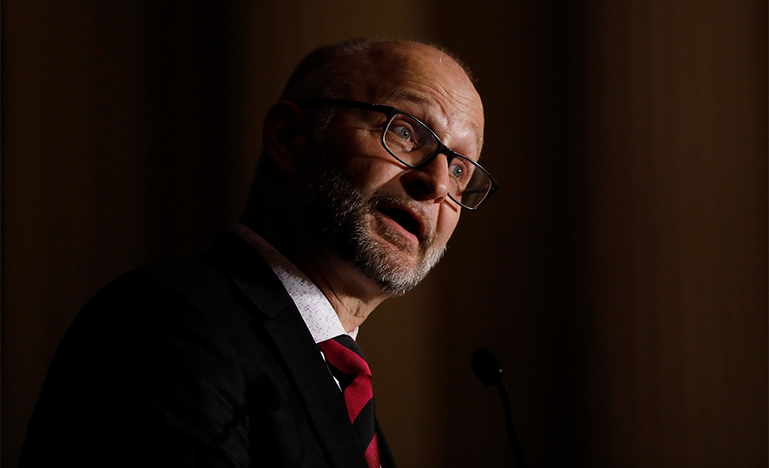

Interview with Justice Minister David Lametti

CBA National caught up with the Justice Minister and Attorney-General ahead of his speech at the CBA's Annual General Meeting. He spoke to us about the government's plans for implementing UNDRIP, repealing mandatory minimum penalties and online privacy.

CBA National: A pandemic question. As Minister of Justice – when you're thinking about some of the measures that the governments at all levels are contemplating – from vaccine mandates to travel bans, how challenging is it for someone in your position to analyze whether government can do what it wants to do, legally?

David Lametti: Well, it is a challenge, but you have to do it. It's part of the role, particularly the role as Attorney-General, and the role of Minister of Justice taking part in policy development. You have to weigh everything. The first question is whether there's an authority to do it, and whether you have the appropriate legislation, the appropriate orders-in-council powers under the appropriate act. And then there are the questions around rights. Section 7 of the Charter is the obvious one — the right to security of the person. That affects vaccine mandates, quarantines — all kinds of things. Regarding the border, has a right against arbitrary detention been breached? So you look at the scope of rights and weigh that against Section 1 of the Charter, which allows reasonable limits in a free and democratic society. In a pandemic, which is temporary, you do the balancing with all the best evidence you have with respect to whatever health policy you're trying to achieve, whether it's suppressing the spread of the virus or trying to protect the health care system and its ability to cope with people who are hospitalized, or even just its ability to test.

N: What about people's level of frustration with some of these measures?

DL: Look, it's been long. I understand the frustration. I'm frustrated and tired of it. And then there's the economic hit. I get it. That being said, the nature of the virus evolves, and the nature of the pandemic response has evolved. Today's response is not the same as two years ago or 18 months ago, or 12 months ago. We still have to continue to assess the best evidence we have and take the best measures we think we can justify in terms of infringement of rights.

N: You have other legislative items on your plate. I want to get your thoughts on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, now in force. It stipulates that the government must report annually on progress in its implementation. Taking a longer view, what do you hope progress will look like?

DL: It's going to take time, but it will have as great an impact and as positive an impact as the Charter [of Rights and Freedoms] has had on Canadian history. I think the document itself will become one of the foundational documents in the constellation of our critically important constitutional and quasi-constitutional documents. I think UNDRIP will be no less than that. In five, ten, twenty, or thirty years, we will begin to see a major positive transformation in Canadian society as we live up to the promise of Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples living in this space as a society that isn't built on colonial premises. I am not naïve about the hard work it will take. It will take a mindset in which we're open to new possibilities and open to working together and listening. And frankly, non-Indigenous Canadians have never had to do that until now. But we've begun that process to build the trust and the relationships. We now have a call out for Indigenous leadership to define what UNDRIP means to them. We're going to work together to develop an action plan with various Indigenous leadership groups in Canada because there isn't any symmetry in those structures. We've bolstered our capacity to interact with Indigenous peoples in the federal justice department. And it's going to mean looking at every single thing we do as a government and say, well, what's the UNDRIP lens on this?

N: So, making sure that our laws comply with UNDRIP moving forward. What about the laws that are already on the books?

DL: We have to look backward and develop those action plans with Indigenous leadership to determine what needs to change. Is the implication that we have to ditch the Indian Act? Maybe. Our policy thus far has been to allow Indigenous nations to discard the Indian Act when they feel they're ready. I suspect the UNDRIP process itself will push a lot of First Nations and a lot of Métis to decide that the Indian Act is no longer for them and move beyond it. And we'll work with them to do that.

N: Recently, you signed an agreement with BC to develop an Indigenous justice strategy. What are you hoping that agreement will produce? And do you think it's going to serve as a model for other parts of the country?

DL: I want to gently remind you of the most important partner involved. It was a three-way agreement with the BC and the First Nations Justice Council, and it might be a model in some places and spaces. And to the extent that others will follow it, and [adapt] it, it could be transformational. We are investing in Indigenous justice centers that give a 360-degree wrap-around set of services and supports to Indigenous people who come into contact with the justice system. It means treating the real problems — poverty and alienation and intergenerational trauma, problematic addiction — with the appropriate supports grounded in the community and grounded in Indigenous traditions and normativity. It helps us address the tragedy and the shame of over-incarceration of indigenous peoples in our system. It gives us better outcomes. It gives us more holistic results. We have a community justice centre model, which we're also funding, for pilot projects focused on Black Canadians that could be potentially transformational.

N: You've introduced Bill C-5, which would repeal mandatory minimum penalties for drug offences and some gun-related crimes. But many will remain on the books. What does your government say to those who criticize your government for not going far enough to address the over-incarceration of Black and Indigenous people?

DL: This is a first step. I'm the first Justice Minister that I can remember that's reversed minimum mandatory penalties. We have targeted a specific number of offences that contribute to making Indigenous and Black people particularly over-represented in the criminal justice system. We're also bringing back the possibility of conditional sentence orders, which allows us to use Gladue reports, community justice centres or Indigenous justice centres as a way of allowing a judge to craft a sentence, and to keep something out of the criminal justice system. So those two [measures] working hand-in-hand is a big step along with diversion [programs] for drug offences, which is the third part of the bill. It will help us get those incarceration numbers down proactively, and I think people will become comfortable with the idea that minimum mandatory penalties don't work. There are maximal sentences where people will still get treated as they're supposed to. And we haven't touched a lot of crimes in addition to homicide and sexual assault. We also haven't touched drunk driving, where there's a great community outcry for very stringent sentencing.

N: A proposed resolution at the upcoming AGM calls on the CBA to consider new approaches to help low- and middle-income Canadians who lack meaningful access to civil legal services. What can the federal government do to help get the ball rolling on the modernization of our justice systems?

DL: So we had a bill in the previous parliament, Bill C-23, that was directly a result of the pandemic and listening to provincial counterparts about making remote proceedings easier, while ensuring fairness to the accused or others. We promised to reintroduce [the bill]. We're also working with the provinces to improve access to justice, whether by making criminal legal aid and legal aid for immigrants and refugees more effective, or on pilot projects to set up sexual assault courts, or other kinds of specialized courts, through family law reform, for example by offering better access to mediation and forcing conciliation, mediation as steps under the Divorce Act. We've done some of this and we're always open to working with the provinces to improve access to justice across the board. And I, as Minister of Justice, am always trying to get resources to improve legal aid and other parts of the access to justice system.

N: Over the last few years, there's been a push to make sure our judiciary better reflects the diversity of Canadians, and this government has made some progress on that front. At the same time, there has been criticism from some quarters that the application process to becoming a judge is an obstacle and tilts the playing field away from racialized candidates that are discouraged from applying. How do you respond to that?

DL: I have heard those comments. And we are responding to them. We put into place judicial appointment committees that we try to make representative and diverse, that vet the applications across Canada in various jurisdictions and at the Federal Court. They're presenting me with lists of highly recommended candidates from whom I can appoint. It's a rigorous process. And since our government took over, 52% of the persons appointed or elevated have been women. We've increased numbers for various equity-seeking groups — racialized Canadians, LGBTQ2+ Canadians, Indigenous Canadians. But it's still a challenge and part of making the system better is making sure our JACs are aware that we're not looking for one profile, that we're looking for many profiles. Some lawyers have gone back to serve their communities and end up doing a lot of what we used to call solicitor's work, and not necessarily a great deal of court advocacy. How do we make sure we don't have a bias against that group because they're not in court as often? Or because they don't have contact with judges in the court system? They do other things in service to their community — valuable legal services. Many are outstanding candidates for the bench.

N: It seems that every year there's a new emerging technology having a huge impact on how we communicate. And it's one of your government's priorities in to update our online privacy laws. Can we expect something different from C-11, which died on the order paper before the election, or is it going to be a similar bill?

DL: This has been an area of interest for me, a professional area of interest for me for my whole career, when I was an academic and now. And you're right to say the technology has changed. We have to react in terms of governance as a government. Part of it is the privacy picture, and we did introduce C-11 last time, which targeted personal information that private actors hold in the Canadian context. We promised we would reintroduce that kind of privacy legislation, which also brought changes to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner. I can't say what we'll reintroduce because that would breach the rules of parliamentary privilege. But we did promise that we would introduce something like C-11 again if we came back into government. What is left, which is within my purview, is the Privacy Act, which covers the information held by government. It's a priority and we've been working through consultations on that Act.

This interview has been edited and condensed for publication.