Overdoing the override clause

Undermining fundamental rights through repeated use of section 33 misses the entire point of having an entrenched Charter of Rights and Freedoms. A first instalment in our series on restoring trust in our legal institutions.

When the notwithstanding clause was rolled into the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, it was seen as a nuclear option – an instrument to be used in urgent and exceptional circumstances.

But given the uptake in recent years, critics say section 33 is a time bomb that's now gone off, posing yet another threat to relations between Canadian citizens and their institutions.

Although the Quebec government initially rolled it into every piece of new legislation between 1982 and 1985 as part of a political protest of the new constitution it never signed onto, elsewhere in Canada, it sat on the shelf. For over 35 years, there were occasions where other provinces made attempts and threats to use it, but Saskatchewan was the only other province that ever did. In 1986, the government there used it during a labour dispute with provincial workers to shield back-to-work legislation.

Most famously, Quebec invoked the notwithstanding clause to override minority language rights in the wake of the Supreme Court's 1988 decision in Ford v Quebec (AG), which struck down an unconstitutional part of the province's language law that restricted commercial signs in any language other than French.

Things were quiet on the notwithstanding front until 2017, when Saskatchewan introduced legislation invoking the clause so that the government could keep funding students attending public or Catholic separate schools, regardless of their religious affiliation.

That seemed to mark a shift, as since then it's been increasingly used by governments looking to get their way with legislation, and often pops up in campaign and populist rhetoric.

In 2018, the Ontario government threatened to use the clause after a judge struck down legislation reducing the size of Toronto city council. Then in 2021, Doug Ford became the first Ontario premier to use section 33, invoking it to push through a bill limiting third-party election advertising after a judge found it was an unjustified infringement of freedom of expression.

In 2019, the New Brunswick government included the notwithstanding clause in legislation to eliminate non-medical exemptions to vaccination rules, but later removed the clause at committee.

Also in 2019, Quebec introduced Bill 21 to prohibit the wearing of religious symbols by public sector workers. In 2021, the government tabled Bill 96 to reform Québec's language laws. Both pieces of legislation included the notwithstanding clause as a pre-emptive shield from the courts.

During the 2017, 2020 and current Conservative leadership race, candidates have been quick to say they'd invoke section 33 for an array of issues. And in Alberta, UCP leadership candidate Danielle Smith has said her first act as premier would be to adopt a Sovereignty Act to allow the province to ignore federal laws it didn't like – which would seem to require broad use of section 33 – and opt out of areas of federal jurisdiction.

So, what's driving this uptick in use and perception that the notwithstanding clause is a magic wand that can be waved to make rights disappear?

"Honestly, I think it's just a matter of imitation," says Leonid Sirota, associate professor at the Reading Law School in the UK and founder of the Double Aspect blog focused on Canadian public law.

He says given how disruptive it would have been for the Saskatchewan government to overhaul school funding, there was academic and public support for what it did in 2017. That prompted governments in Ontario and New Brunswick to take notice.

"There was a sense of certain things that aren't done, but then it turns out this thing can be done. Nothing particularly bad happened; the sky didn't fall. We have this tool in our toolbox," Sirota says. "I'm not sure there's anything more to it than that. Politicians always want to get their way."

Admittedly, Quebec "is a different beast," as it never signed on to the Charter. The provincial government has called section 33 "the parliamentary sovereignty provision," and Bills 21 and 96 explicitly include it as an overarching constitutional principle.

"They assert that the legislature has the ability to decide everything in a way that Saskatchewan and Ontario never did," says Sirota. "Ironically, [it's] an assertion of this pure Westminster, British conception of parliamentary sovereignty."

During the Bill 21 debates, he says Justice Minister Simon Jolin-Barrette's framing of the issue was noteworthy. He justified the use of section 33 by saying the province has the responsibility and power to decide these things within the confines of the legislative assembly without referring to the courts at all.

At the University of Sherbrooke, constitutional law professor Maxime St-Hilaire says for a long time, there was a sense of orthodoxy regarding the Charter and the court's power to have the last say. There was a consensus regarding section 33, that it would be an exceptional gesture for legislators to invoke it. But that orthodoxy is under pressure and being challenged outside of Quebec.

"There's also a rise in academia of political constitutionalism as opposed to legal constitutionalism," he says, noting that part of the former is the idea that legislatures should be considered an alternative to courts when it comes to interpreting rights.

"This is not specific to Canada. It's a global phenomenon. Both right- and left-wing populism in Europe is a symptom of this. Brexit is an example of this. There's a reaction towards the orthodox liberal globalized model of human rights and constitutionalism (inherited from the aftermath of the Second World War). Some people are seeing the limits of it – of globalization, of liberalism and of the judicial constitutional review of legislation, especially that which is based on rights. It's being challenged. There's no reason Canada would have totally escaped that."

For his part, Quebec Premier François Legault has defended his government's use of the notwithstanding clause to override rights with Bills 21 and 96, insisting they express "the will of a majority of Quebecers."

And yet, protecting the rights of minorities goes to the heart of the Charter – and undermining them to appease the whims of the majority is antithetical to it.

"To just say that this is the will of the majority, it does really miss a lot of the reason why we have an entrenched bill of rights and judicial review of government action," says Cara Zwibel, director of the fundamental freedoms program at the Canadian Civil Liberties Association.

"(Legault) doesn't display a good understanding of what the notwithstanding clause is there for. To me, it's for cases where you've gone back and forth with the courts, you're tackling a difficult issue and there's disagreement about a right or the scope of a reasonable limit and the government decides, 'ultimately we know best.' But it's not just, 'this is what people want, and we don't care how it affects minorities.' I would have thought the Charter shouldn't allow that to happen."

"We had human rights acts and codes, and we had a federal declaration so we had quasi-constitutional human rights acts before 1982," says St-Hilaire. "The whole point of having the Charter was to protect rights at a level that is above legislation."

In reviewing legislative debates around invoking the clause, Sirota says he's found a real lack of thought or discussion about the individual rights being overridden in the process.

He says if legislatures took their responsibilities seriously, they might get at the philosophical truth about as often as judges do when reviewing legislation.

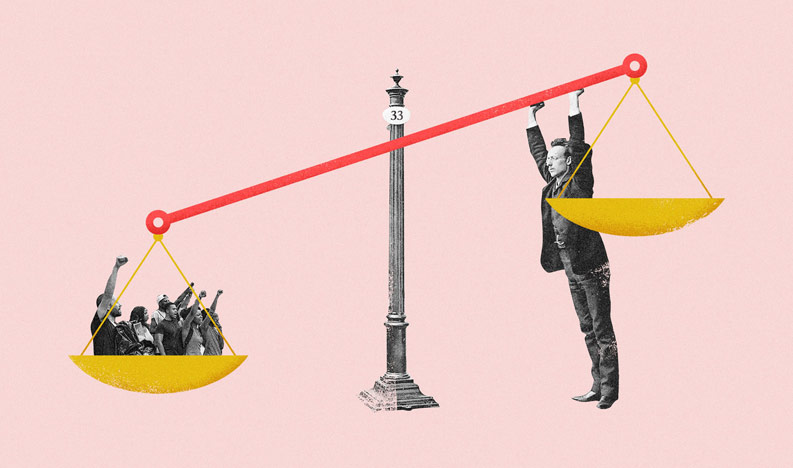

"But that's not what I see in the debates. What I see are arguments about why they want to enact the policy but no consideration of what this does to individual rights. There's only one side of the scale. I don't think rights are getting a hearing in the legislature. And that's a problem," he says. "Politicians will always be tempted to read it in a way that grants them more power than the Constitution actually does."

Kerri Froc, an associate law professor at the University of New Brunswick, says governments' pre-emptively using section 33 to thumb their noses at the Charter and judicial review would be completely foreign to the drafters and ratifiers of the Charter. Politicians are "plugging their fingers in their ears and trying to pretend that the Charter doesn't exist," she says.

Sirota thinks the distinction between pre-emptive and reactive use is overdone. For a new issue, such as mandatory vaccination, where there is no precedent and no one knows how it will play out, he says there's an argument to be made for litigation to test it in the courts and to get guidance. Then if a legislature disagrees and has its own view of the constitutional situation, it can invoke section 33.

For that reason, New Brunswick's attempt to use the clause without any guidance to short-circuit the judicial process was "a bad idea."

But with Bill 21, "Quebec government's legal advisors know perfectly well how those provisions would have fared in the courts – they would have been struck down," Sirota says. "Why would we demand that they go through the whole rigmarole of litigating this in the courts, getting smacked down, and then re-enacting this with the notwithstanding clause?"

Zwibel disagrees. She says even if a government has invoked the clause to shield themselves, as part of democratic accountability, a court should still be able to say, absent the notwithstanding clause, this is a provision that we think violates the Charter in a way that's unreasonable. That way, people can decide if they want to vote for a government that has chosen to have a law in place that violates and restricts rights.

"Even with Bill 21, though the court was of the opinion they couldn't strike things down because of the notwithstanding clause, they did make statements about the reasonableness of the legislation and the fact some of the measures restrict rights," she says.

"The government can convince people it's not a violation of anyone's rights, so if there's another voice out there, I think that can be powerful. That will change some people's minds and cause them to think, 'maybe we shouldn't do this.'"

Further, increased use of the clause is feeding skepticism about the extent to which the constitution can be a protective tool. And the fact that governments are using it to shield themselves from criticism is "particularly concerning."

"People are rightfully concerned about whether we really have meaningful protections, if all it takes is a majority in a legislative assembly to say this doesn't get scrutinized in the courts in an effective way," Zwibel says.

"I think my biggest concern is the government's attitude about it (specifically in Ontario). It's very flip about the whole thing. This is something we can do and it's the will of the people."

Federal Justice Minister David Lametti has discussed the possibility of seeking a Supreme Court reference on using the clause. He said pre-emptively rolling it into its legislation cuts off legal analysis and political debate. "In a democracy, this is not desirable," he said.

Zwibel says she can't imagine what a reference on the clause would look like or how it would work.

"There's room for judicial interpretation around when and how the clause can be invoked, but I tend to think it might be better for courts to deal with the cases where it is invoked and enunciate those principles. I don't know how it would pan out if you asked the questions in more of a vacuum."

Given that Bill 21 is now tied up in litigation and working its way through the courts, Froc says the issue is going to the Supreme Court one way or another. She says the court's decision in Ford "is ripe for a reconsideration," as it found that section 33 is only subject to minimal procedural requirements. Governments only have to refer to the Charter provision its law is looking to override to shield it, or they can make a blanket statement that the law operates notwithstanding all the rights referenced in section 33.

"That was maybe okay in 1988, but it doesn't fit the bill today where you do have this potential erosion in the legitimacy of the Charter," Froc says, given that it's almost pro forma to talk about the notwithstanding clause if you don't want to comply with it.

She suggests there should be an obligation on a government to draw the public's attention to its use of the clause and seek input before doing so. Like Zwibel, she sees a benefit in judicial review even when it is invoked to talk about how the law infringes on rights. That would inform legislatures as well as citizens.

In contrast, St-Hilaire thinks the court in Ford got it right. If the court sees fit to shift from a formal judicial review to a more substantial review, the current challenges to the liberal rule of law, as well criticism of the critiques of government by judges, would gain even more legitimacy.

Ultimately, Sirota says there's not much the courts can do. If the federal government does refer this to the Supreme Court, it will be "as open and shut a case as there could be."

There have been calls for Parliament, which has never invoked the clause, to unequivocally declare its opposition and commit to never use it. That could happen by passing a motion, resolution, or law in the House of Commons, adopting a blanket policy against its use or committing to intervene in cases where it is.

Sirota says a law would likely be invalid, as the Constitution says the power to use the clause exists. "I don't see how Parliament can override that."

While a motion is doable, it only expresses the feeling of the present Parliament and doesn't bind. The same is true of a policy.

"My sense is that all these theories put forward by smart people about implicit limits on the notwithstanding clause, they don't hold any water at all," he says. "I think it's a waste of time, clutching at straws."

Ultimately, formal changes are not what's needed.

"The change that needs to happen is in the hearts and minds of people, the sense that this is not a done thing," Sirota says. "That is beyond the reach of legislation, parliamentary motions or executive pronouncements."

Zwibel thinks it would be an important move for the federal government to stand up and declare it won't ever use the clause, as she believes its use must "become politically costly again."

If a government chooses to use it, they need to be up for the hassle and the litigation that will follow. But despite all the talk in Alberta and Conservative leadership races about using the clause, she's hoping that's not actually the case.

"A lot of the bluster relies on an audience that doesn't necessarily have a good understanding of how our institutions actually work," Zwibel says. "And some of that is just based on ignorance of the reality of what the constitution says or a hope that the general public doesn't know what it says."

Froc says for section 33 to become politically costly again, academics and the media must do a better job informing the public.

"We have to find ways to cut through that noise and give people the information that they need. There's a heavy responsibility on people that know about the Charter to go on and provide information to the public."

That means working to find a middle ground between the legislative supremacists and the judicial supremacists, something that will appropriately balance all legitimate Charter interpreters, including the public and the legislators.

"People like me and professionals like lawyers, we denigrate the people that are attracted to populist movements at our peril," she says. "We have to find a way to talk across differences. I think it makes it harder when there are politicians out there blowing smoke and feeding this misinformation about the constitution."

St-Hilaire's been disappointed by the response from constitutional law professors to Quebec's use of the notwithstanding clause. The arguments against it have been "weak," and he says it's clear people have been taking for granted the arguments for strong constitutional review of legislation based on rights.

"What I have been witnessing over the past few years is a much stronger case than I would have imagined in favour of a non-exceptional use of section 33," he says. "We need less arrogance from the orthodox side. It's being seriously challenged and we need a much better conversation. People who disagree with this will have to come up with strong arguments, not just some dogmatic discourse."

Sirota says for most of the Canadian legal establishment, the Charter is a living tree that can change with the prevailing morality of the times. Now, the tree is growing and bearing fruit, and it's not to everybody's taste.

"The dissident opinion is that constitutions aren't meant to be living trees because of precisely this," he says. "The change in how people think about them is not always going to be in the direction of ever more rights for ever more people."

He says he's concerned because there is a possibility the Charter could become a dead letter.

"We don't know how it's going to play out, but there is every reason to be worried. If we want to have some kind of constraint, that has to come from what people believe in."