Is presidential envy behind the renewed push of Henry VIII clauses?

Some observers say they should be unconstitutional, given their end-run around debate and the legislative process

Shortly before the summer break, the federal Parliament and the Ontario legislature passed major project legislation containing "Henry VIII clauses," which delegate significant authority to the executive branch of government in each respective jurisdiction.

To date, courts have generally been deferential to these clauses and considered them to be constitutional, though some observers feel that shouldn’t be the case.

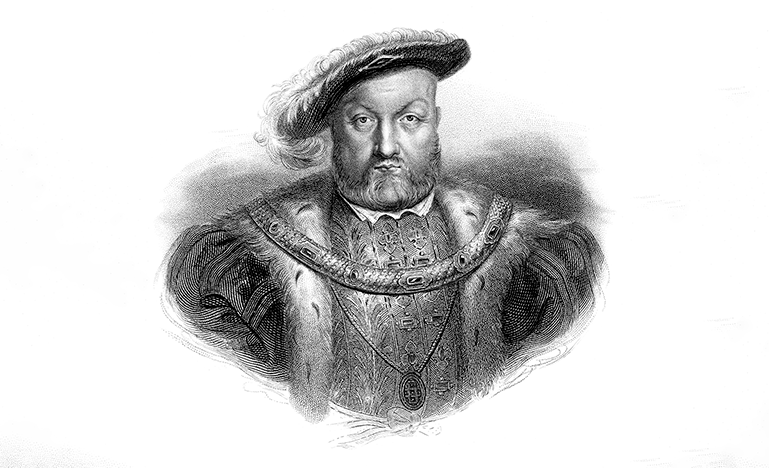

The term Henry VIII clause stems from the Statute of Proclamations 1539, which was Thomas Cromwell’s attempt to legislate King Henry VIII’s desire to rule by decree and bypass Parliament. The law was repealed in 1547, but it was one of several attempts by British monarchs to continue using proclamations. This eventually led to the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the Bill of Rights, which entrenched parliamentary sovereignty.

In modern parlance, these clauses allow the executive to change or repeal existing statutes through regulation rather than the normal legislative process. They were largely unused in Canada until the conscription crisis and the use of the War Measures Act brought on by the Great War, at which point the Supreme Court of Canada ruled 4-2 in Re George Edwin Grey that the clause was permissible.

More recently, the Henry VIII clause in the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, which allows for incremental adjustments to the pricing mechanism on an ongoing basis, was not ruled out of order by the Supreme Court. It was, however, the subject of a dissent by Justice Suzanne Côté.

Constitutionally okay doesn't equal a good thing

Paul Daly, law professor at the University of Ottawa, says that from a constitutional perspective, there isn’t really a difference between the clause in the GGPPA and the more recent legislation.

“Does it make a constitutional difference that Bill C-5 (federally) or Bill 5 in Ontario go further than merely allowing cabinet to tinker with a detailed regulatory scheme?” he asks, noting he doesn’t think so.

“The constitutional questions remain: Did Parliament or a legislative assembly abdicate its powers? If it hasn’t abdicated its powers and hasn’t violated any other provisions of the Constitution, then giving cabinet the ability to modify the statute book by regulation is not constitutionally prohibited.”

That said, the fact that something is not constitutionally prohibited does not mean it’s a good thing. Daly says one can plausibly believe that the Henry VIII power in the GGPPA was more acceptable because it was more narrowly tailored and arguably necessary for the regime to function. In contrast, something like Bill C-5 is a general power to dismantle any regulatory barrier that might be standing between a desirable project and it being completed.

The purpose of the GGPPA and the statutory scheme was very clear. While the purpose of C-5 is clear, there isn’t much detail in the statutory scheme.

“It’s unpredictable as to how it will be used,” Daly says

Ontario’s Bill 5 is even more open-ended than the federal Bill C-5. It allows the government to declare a special economic zone where one particular person or proponent can be exempted from relevant provincial and municipal laws or regulations.

“There is no guidance in that statute,” Daly says.

“Here is a contrast between the federal legislation and the provincial legislation. The federal legislation at least has a statement of purpose and criteria for how you designate a project. That provides some substantive guardrails on the exercise of the power.”

There are also procedural requirements, including a consultation requirement with Indigenous people, which is not part of the Ontario legislation.

An unconstitutional case to be made

Stephen Armstrong, associate at Three Crowns LLP in Paris, France, has written a paper for the Runnymede Society arguing that Henry VIII clauses should not be considered constitutional. In it, he points to Côté’s dissent in the GGPPA reference and how she distinguished between the emergency situation of wartime powers from the earlier Re Grey decision and the powers used in the GGPPA.

Armstrong notes that if he were advising clients, any argument that these clauses are unconstitutional would be an uphill battle. However, the Supreme Court occasionally departs from previous decisions after time has passed and attitudes change.

“I would say it’s very possible that the Supreme Court could walk back parts of that decision and add some qualifications,” he says.

“Do I think they would adopt my position? I wouldn’t think that would be the most likely outcome.”

In his paper, he relied on more recent Supreme Court of Canada jurisprudence to make his arguments, so he thinks there is a case to be made, but predicts something less extreme than his position would be adopted.

However, Armstrong says there is talk in legal circles that legislatures looking to employ these clauses should adopt a clear policy within the statute that can be policed by courts. They could also ensure that the body that receives the delegated power is one over which the legislature has control. In theory, the legislature has control over the cabinet.

He says granting governments more power to cut through red tape to get major projects built always sounds like a good idea at the time.

“Nobody seems to think about the potential for misuse when they’re enacting the legislation, but once it’s on the books, it’s too late to do anything about it.”

Joseph Redman, a partner at Shores Jardine LLP in Edmonton and chair of the CBA’s administrative law section, suspects that presidential envy may be leading this renewed push to use these clauses.

“There is a trend or a movement toward the executive seeking or asserting more of that authority, whether that be through Henry VIII clauses, but you see it popping up in legislatures across the country,” he says.

The auspices of the cutting of red tape often surround it.

“There is a view, whether that is driven by the executive or not, that the legislative role they would fulfil is just regulation getting in the way of getting business done. We haven’t seen a court strongly rebuke that to date.”

While Redman doesn’t know if a direct link from American policy can be tied to the use of Henry VIII clauses, he says there’s certainly a more active executive and testing of the limits of the executive authority and the courts.

“Whether tangentially or directly, there is some translation to what is going on up here. The executive is a little more willing today than they were 20 years ago to test that authority. I think the pendulum has swung in that direction, and I’m curious to see if we end up with pushback.”

Daly worries that normalizing these clauses, which allow the executive to legislate, will lead to further concentration in one branch of government.

In any system of separation of powers, the goal is to have checks and balances, and Henry VIII clauses remove an important check on the executive.

“As the name suggests, it is designed to empower an executive in a way that is not constrained by law,” he says.

“If these laws on the statute book are valuable, and there’s reason to think they are, they shouldn’t be subject to being repealed, modified, deleted, or made to be inapplicable at the stroke of a ministerial pen.”

An abdication of power?

Daly also thinks that the test in court as to whether these clauses abdicate responsibility is very permissive.

“The Ontario legislation, in my view, comes close to an abdication of power, effectively handing the legislative power of the province to the executive. True, it’s confined to specified special economic zones, but in the absence of any substantive or procedural guardrails, I think there is a plausible case that this is unconstitutional.”

He says a lower court might be able to find Bill 5 unconstitutional based on the abdication principle without upsetting the long line of cases that established that broad delegations of power are permissible.

Armstrong says legislatures are where the issues of the day are supposed to be debated. It’s where members of Parliament and senators can make any speech they want on a bill and voice issues that aren’t necessarily going to be voiced by cabinet or the civil service that develops mechanisms that cabinet adopts. These clauses do an end-run around that process.

“With more Henry VIII clauses, cabinet will not need to consult the legislature, and that’s very convenient for cabinet. Perhaps certain objectives will be implemented, but it seems to be part of an unfortunate trend of the first minister dominating the executive and the legislature in Canadian politics.”