Legislative power and liability

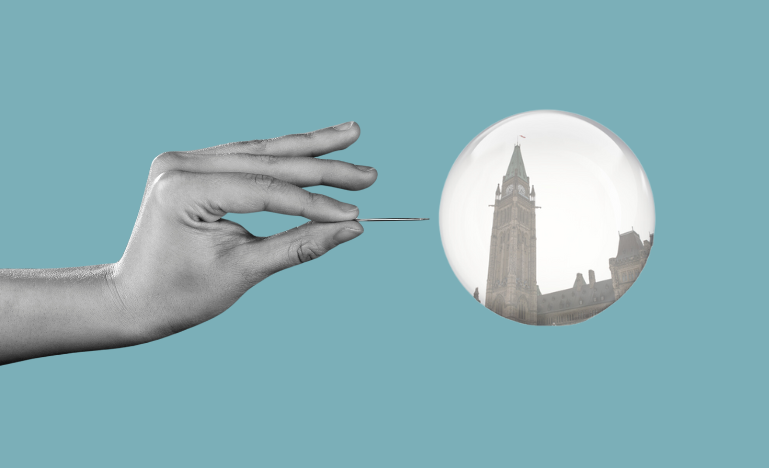

Can the Crown be held liable for unconstitutional legislation?

It’s never easy to get the Supreme Court’s attention. Appeals make it to the SCC level only when someone’s asked a legal question so big that the top court alone can answer it.

The SCC is about to consider the Attorney General of Canada’s appeal in the case of Joseph Power. The case turns on a very big question — whether governments can be held liable for damages for passing legislation later found to be unconstitutional.

Lawyers love speculating about which way Supreme Court justices might jump. The very fact the SCC chose Power’s case for consideration suggests the court is preparing to clarify an awkward point of law, says Peter Spiro, counsel to Monkhouse Law.

“The week Power came up, there were nine cases being considered for leave to appeal [to the SCC] and Power was the only one to get it,” says Spiro, who specializes in corporation law and civil litigation.

Joseph Power committed two crimes in the 1990s and spent time behind bars. He inquired about a pardon in 2010 but never followed through. A year later, his employer found out about his criminal record and suspended him.

Power applied for a pardon in 2013. By that point, the Harper government had passed two laws — the Limiting Pardons for Serious Crimes Act and the Safe Streets and Communities Act — with transitional effects that retroactively limited the circumstances in which pardons could be granted. The laws made Power permanently ineligible to obtain a record suspension.

His ineligibility for a pardon also made Power — who was working as a medical radiation technologist at the time — ineligible for membership in the provincial body governing his profession. He lost his job as a result. The courts later struck down the transitional provisions that kept him from obtaining a pardon as unconstitutional. Power brought an action against the Crown seeking damages.

Section 24 of the Charter says anyone whose rights under it have been “infringed or denied” can apply to the courts “to obtain such remedy as the court considers appropriate and just in the circumstances.”

To date, the only cases to see compensation under S. 24 have been ones involving Charter rights violations by governments and police services that failed to follow the law. Before the Charter, governments in Canada enjoyed absolute immunity from lawsuits claiming damages resulting from unconstitutional laws.

Section 24 opened the door to compensation — and in Mackin v. New Brunswick (Minister of Finance), the courts established a test: governments can be held liable for damages stemming from legislation later declared unconstitutional only if it’s clear they acted in “bad faith.”

“Laws must be given their full force and effect as long as they are not declared invalid,” says the decision in Mackin. “Thus it is only in the event of conduct that is clearly wrong, in bad faith or an abuse of power that damages may be awarded.”

‘Bad faith’ is hard to prove; the plaintiffs in Mackin couldn’t do it. “Establishing subjective intention like that is a very high evidentiary bar to get over,” says Megan Stephens of Megan Stephens Law. She’s acting for the David Asper Centre for Constitutional Rights as an intervener in the case.

“As such, it’s pretty close to absolute immunity already.”

Bad faith in a legislative process is almost impossible to establish. Cabinet deliberations are confidential and inadmissible as evidence.

“Even if a whistleblower came forward with evidence that cabinet passed a law knowing it was unconstitutional, that testimony would violate cabinet privilege and be ruled inadmissible,” says Spiro.

“I don’t think any court is going to suggest interviewing cabinet ministers or violating cabinet confidentiality.”

Josh Dehaas is counsel for the Canadian Constitution Foundation, an intervener in the case. The CCF argues the standard in Mackin should stand, and governments should not be absolutely immune from damages. Dehaas acknowledged such claims are only likely to succeed in rare circumstances.

“We are not proposing that individual legislators be hauled before courts to testify,” he said. “You could envision a situation where a politician acknowledges in a legislature that a bill is unconstitutional, but he doesn’t care; he’s going ahead anyway. In that circumstance, the court could simply examine the transcript in Hansard.

“Bad faith is going to be very hard to prove, especially given the effect of cabinet confidence. Clear wrongness, recklessness and wilful blindness will be somewhat easier to prove based on evidence like Hansard, but those situations will also be very rare, which is why we believe a clarified Mackin standard is appropriate.”

So why is the Attorney General of Canada taking Power to the top court if the Crown already enjoys something close to absolute immunity?

The New Brunswick Court of Appeal rejected the AG’s arguments in Power — that subsequent rulings have indicated Mackin applies to state conduct under the law, not the enactment of laws, and that opening governments to damages would have a “chilling” effect on legislators. The court said it was bound by Mackin’s precedent.

Spiro suggests the Attorney General of Canada appealed the case to the Supreme Court to clarify the Mackin test. He also says the high court might consider refining the test along the lines suggested by another intervenor, the Attorney General of Ontario — which complained in its factum that “the Mackin test fails to provide sufficient guidance to identify the rare circumstances under which the Crown can be held liable in damages for the enactment of unconstitutional legislation.”

“Ontario submits that Charter damages should only be available for the enactment of unconstitutional legislation where: (1) there is binding authority that directly determines the constitutional issue; and (2) the defending government does not have a credible legal argument for distinguishing that authority,” says the Ontario AG’s factum.

“Perhaps the ‘clearly wrong’ aspect of the criteria stated in Mackin can be transformed into an operational definition,” says Spiro. “If the legal analysis at the time of enactment, by neutral third parties, overwhelmingly warned that it was unconstitutional, that might be sufficient grounds for a judicial inference that it was done in bad faith.

“In the case of the parole law, I believe the vast majority of lawyers in the field saw that it was unconstitutional.”